Food forests draw from Indigenous culture and holistic ecosystems

by Kimberly Leeper, Beacon Food Forest

Where can you find food, medicine, beneficial wildlife-pollinator habitat, healthy soil, natural pest control, beautiful biodiversity, a sense of well-being, low maintenance, and fun? In your very own food forest (aka, edible forest garden) that you create!

I discovered food forests a dozen years ago and have been inspired and involved in them ever since—in urban residential spaces, and at the Beacon Food Forest in Seattle. Food forests protect the soil’s natural biome, as there is little digging or tilling after planting. They make their own mulch with leaf litter, which also feeds the soil by recycling nutrients. Deep roots mean less watering, and the tree canopies and taller shrubs shelter the lower-growing plants from stressful midday heat. These self-sustaining gardens require far less weeding, too. Often, friendly birds or ladybugs keep pests in check. I’ve seen year-round harvests of spring greens, and then summer berries and fall apples, with root crops in colder weather—depending on the climate.

Having personally experienced their many benefits through my work, I love sharing all that I’ve learned about them.

My journey with food forests began with learning about nature, Indigenous cultures, and then permaculture. This is a holistic design system that looks at natural systems and patterns and then emulates them to design our whole human settlement — shelter, water, energy, food, waste, etc. — to integrate harmoniously with nature. Permaculture is based on Indigenous knowledge and regenerative land-care practices. The Ethics of Permaculture are Earth Care, People Care, and Fair Share, and there are 12 permaculture principles.

Food forest basics

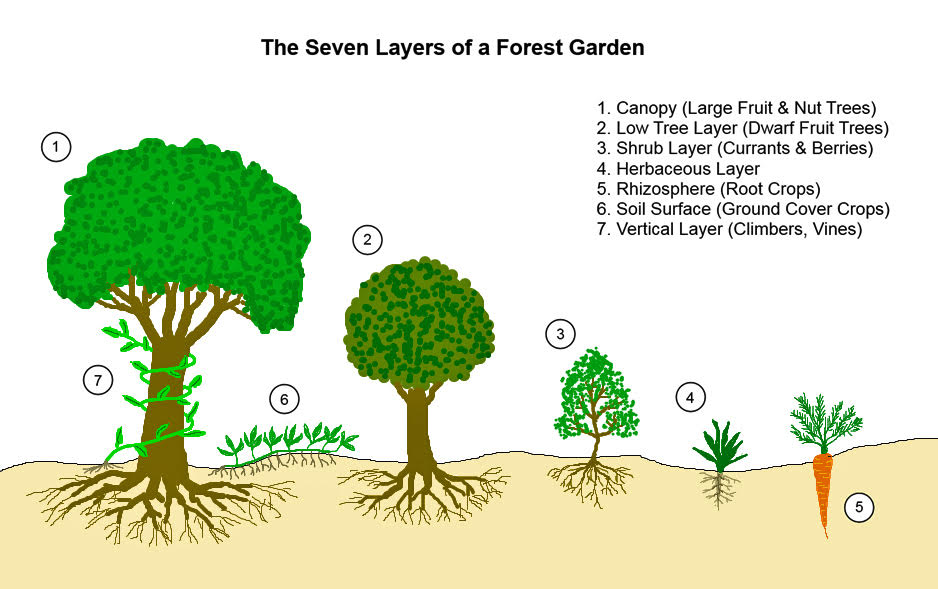

What is a food forest? It’s a method of growing food using a variety of perennial plants that’s similar to a woodland ecosystem. Because the forces of nature are always moving the land towards becoming a natural woodland, it takes less energy to maintain a food forest, especially compared to our usual highly cultivated agricultural approach using a lot of annuals. Food forests exist all over the world; one in Morocco is 2,000 years old! The individual plant species occupy a variety of vertical layers, maximizing the use of the sun’s energy, relationships between plants, and water storage and nutrients within the soil.

The plants are layered. There’s a tree canopy with the largest trees, then smaller trees, larger shrubs, smaller shrubs, perennials, vines, groundcovers, and then roots and tubers. Every food forest is different because they are designed around the needs and requirements of the users. Some food forests have more trees while others focus on a perennial herbaceous plant layer.

Guilds

The building blocks of food forests are called “guilds.” This is the foundation of your food forest design. You can have a single guild or you can have several that interconnect to make up your food forest. A guild in a food forest is a community of plants working together, with each type of plant occupying a layer and performing different functions (providing nutrients, protecting soil, attracting pollinators, etc.), usually centered around a main tree. An example of plants to choose for an Apple Tree Guild containing seven plant species:

- The apple tree blooms in a brief, furious burst that is an early bonanza for pollinators, and then produces summer shade and crisp, fall fruit.

- Goumi, a large shrub, is a great nitrogen fixer, resource for pollinators, and berry producer.

- Clove currant, a medium shrub, also attract pollinators and produces berries.

- Sorrel is great for early leafy greens and mulch throughout the growing season.

- Lupine, another nitrogen fixer, offers a long blooming season for local pollinators.

- Cucumber, a vertical plant and late-season food crop, requires industrious pollinators.

- Strawberries provide ground cover, attract hungry pollinators in early spring, and supply delicious fruit as early as May Day.

Important questions to ask

When you’re designing your food forest, there a several important factors to keep in mind.

How much does it cost?

Let’s start with cost. The cost to make a single guild, such as the Apple Tree Guild above (about 225 sq ft; the area of the mature tree canopy) in the Seattle area would be around $250. That’s if the homeowners did all of the work themselves. This cost includes:

- 2 cubic yards of wood chips for sheet mulching over lawn.

- Cardboard that is needed for sheet mulching would be found in your own stash, your neighbors’, or going to local appliance or bike shops. You want big pieces of brown cardboard to cover the soil well to kill the lawn or weeds where the guild will be planted. Take any tape off the cardboard, if you can. You can remove it from the soil later.

- Ten plants bought at local nursery.

- One apple tree (5-gal container)

- One goumi (1-gal)

- One clove currant (1-gal)

- One cucumber (4-in size)

- Two lupines (1-gal each)

- One sorrel (4-in)

- Three strawberries (4-in)

How much space do you have?

It’s important to remember to space the plants so that they have room to grow to their maturity so important to know and keep in mind how large they will eventually get. A food forest guild is typically the canopy line of the central tree at maturity (often 15’ – 20’ around [250 sq. ft.]). For smaller spaces, consider a Columnar Apple tree for a smaller guild. They use only a 6’ x 6’ space. Create several guilds adjacent to each other to build diversity and yield in areas from 1,000+ sqft. Remember to mark your pathways through the areas with stepping stones or wood chips to get around easily for harvesting and maintenance.

How much time do you have?

The amount of time you’ll be living in/around your home. All of your efforts pay off tremendously when you tend your garden for 3 to 5 years or more. Depending on the size of your plants when installed and how well they adapt, you could have an abundant amount of food by year 3 after planting. There’s a saying among us plant people: “First year plants sleep, second year they creep, and third year they leap.” It’s worth paying more to get some 5-gallon fruit trees so you have fruit sooner. Many of the plants I plant are 1-gallon–sized so they have some substance to them. If you are on a tighter budget, you can grow your own plants, salvage plants, or use 4” plants.

What animals are likely to visit?

It’s good to know what animals, insects, and birds you might have in your garden. If you have dogs, you’ll want to add edging around planted areas to deter them from these areas. Outdoor cats also can be problematic in the garden (and to songbirds), but there are ways to deter them, as well. You may have deer or other wildlife stopping in. There are good resources available with how to humanely coexist with them in your area.

Are you ready for seasonal maintenance?

Do you have time and energy to prune and harvest at key points of the year? In Seattle, we often prune fruit trees in late winter before they blossom, and we sometimes thin fruit in the summer. We harvest our fruit trees and berries in late spring to early fall. Your timing will depend on where you live and what plant species you have. Look for resources that are specific to your area. I have a harvest whiteboard where I write down what needs to be harvested each week after observing and working in the garden.

Having around 10 hrs/week for a 5,000 sqft (or less) garden is ideal. It amounts to about 90 min/day to keep up with watering and harvesting delicious fresh food. Maintenance includes some weeding, though that’s usually minimal because the plantings crowd out most of the weeds. The rich rewards make it very worth it! And you might find a willing partner or volunteer to help out if the reward is a share of the bounty.

Where does your water come from?

You will need a water source to establish and maintain your food forest. In Seattle, for example, we have drought conditions all summer, so we rely on irrigation and other methods. Figuring out your watering system before planting will definitely ease the work of growing healthy plants. A few water-conserving tips and tricks apply no matter where you live. You can hand water (outdoor spigots needed), use heavy-duty soaker hoses, put in a simple drip system with timers, or have a local (and ideally, highly rated) irrigation company install a drip system for you.

Design

Let’s say you’re excited to create your own food forest, where do you start? I’m including some suggestions, but you should consult with experts in your area if you need help.

The first step is to take time for your design. Observe and assess your own site well, ideally over the course of a full year of seasons. Record what’s happening with sunlight, water flow across site, soil type, animals, insects, and wind. Get all underground utility lines marked before doing any digging. Make a simple scaled map of your entire landscape noting what will stay, e.g., buildings, infrastructure, landforms, and property lines.

Create a layout with plant guilds and select appropriate plants for your area. Be sure to include all layers of the food forest. Trees are often planted on the north or east side of a landscape, allowing optimum sunlight to enter the guilds. Think about including some evergreen plants in each guild to have more beauty and structure year-round. Over the whole landscape, look for several plant species that bloom each month to support different local pollinators.

Demolition

You can work on the design (and know the design will continue to evolve) while making the space for your plantings to thrive. Begin removing unneeded hardscaping (including asphalt and concrete; reuse if possible), and any unhealthy plants that are diseased or in the wrong place (sometimes they can be gifted or transplanted to a new spot). When working on your site plan, add hardscaping and other construction elements first, including cisterns and rain gardens. Ideally these are installed and working before any new planting is started.

Turn lawn into healthy soil through no-till sheet mulching (pictured), which can be as simple as overlapping brown, biodegradable cardboard over cut down and watered grass. You may need to make more extensive amendments to build topsoil and nutrients where soil quality is poor and compacted. It takes about 6 months for the grass to be converted into rich soil ready for planting.

Let’s plant a food forest!

Start with your biggest plants first. Trees take the longest to grow to maturity. In Seattle, it’s best to plant trees in mid-October through November when they’re dormant and the rainy season has begun. Fall planting gives more time to have natural rain before our summer dry season. Visit a local nursery, landscaper, or garden club to research the best planting times in your area.

Pay close attention to how large all of your plants will be at maturity. This way, your plants will have the best chance to develop a healthy root system and have enough room to grow without crowding the other plants. When shopping for plants, ask for plants without neonicotinoids, which harm pollinators including bees. Take time to plant well: plant in existing soil, dig the hole wide so the roots have room to expand, and don’t plant too deep or too shallow.

Plant shrubs next; then add smaller plants to your guild(s) over time. Start simple with three plant species to create your first guild. Mark off a small path to be able to get in to maintain and harvest over the years.

Growth and maintenance

Figure out a maintenance schedule to meet your plants’ needs. Weed regularly to keep the area clear, especially around new plantings. And make sure mulch is covering the soil surface, 2 to 3 inches, to discourage weeds and keep moisture in. Monitor to see if any pruning is needed. Pruning is a sophisticated skill, so you may want to hire a local expert and reputable gardener to help you start your pruning off well. I recommend using certified arborists for pruning trees, especially if you have well-loved, mature trees.

Verify that your watering system is operating properly before the dry season starts. The timing will be sometime between mid-spring to early fall, depending on your climate and local weather. Keep an eye out for problems with drainage. Watch also for dry plants, as irrigation systems often miss a plant here or there and need to be adjusted.

Harvest and enjoy

Check plants regularly to see if there is anything to harvest, and what insects and birds are visiting. It often takes 3 to 5 years for fruit trees to bear much fruit, and 1 to 3 years for berry shrubs, depending upon what size plant you start with. Sprinkle in annual greens, veggies, and aromatic herbs, so there is always something to harvest. Over time you’ll enjoy an abundance of fruit and veggies for yourself and your family, so likely enough to share with others.

I’ve given you a lot of details to consider here, because I want your food forest to thrive. But I hope you also feel inspired to create your very own food forest! They are true havens of abundance for people, plants, and wildlife. Do visit the Beacon Food Forest if you’re in the Seattle area, or find a food forest near you. I’ve added some resources that provide guidance and outline some building blocks you can use. But there are so many creative and personal ways to design your own guilds and enjoy them your own way.

Additional Resources

Gaia’s Garden: A Guide to Home Scale Permaculture (2nd Edition) by Toby Hemenway

The Permaculture City: Regenerative Design for Urban, Suburban, and Town Resilience by Toby Hemenway

Edible Forest Gardens (two volume set) by Dave Jacke

Practical Permaculture: for Home Landscapes, Your Community, and the Whole Earth by Jessi Bloom and Dave Boehnlein

Permaculture Principles & Pathways Beyond Sustainability by David Holmgren

Attracting Native Pollinators: Protecting North America’s Bees and Butterflies by the Xerces Society

Bullock Permaculture Homestead website

Permaculture Institute of North America professional association

The author:

Kimberly Leeper, a Seattlite since 1995, is a garden educator, regenerative landscape designer, and plant and wildlife enthusiast who specializes in Pacific Northwest native plants, beneficial wildlife habitat, and food forests/edible forest gardens. She has a background in teaching children and adults in schools and in nature, volunteering with community gardens and plant-related endeavors including the Beacon Food Forest, and leading sustainable landscaping companies. She is currently focusing on consulting, coaching, and education.

Kimberly loves inspiring people to think more holistically about their landscapes and the planet and creating foraging opportunities close to home.

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees, at no additional cost to you, by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Make the most of your green space!

Finding the Best SIP Manufacturers

Focus on quality, reputation, and reliability. A SIPS manufacturer far away may still provide better products, service, and value compared to local options.

9 Eco-Friendly Electric, Propane, and Natural Gas Grills

You don’t have to choose between reducing your carbon footprint and enjoying a backyard cookout. Sustainable grilling starts with an eco-friendly fuel source.

Can Fire Resistant Landscaping Save Your Home from Wildfire?

If you’re worried about the wildfire threat to your home, landscaping firm FormLA shows how beautiful fire resilience can be.