By Blake Thomas

Inviting ingenious, sustainable design and cutting red tape are two tools that government can wield in solving the housing crisis. Affordability, however, remains an obstacle for most first-time homeowners. With their smaller footprints and low, low construction costs, accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and tiny homes can help. Whether they’re providing additional income or housing extended families, ADUs can foster home ownership. Tiny homes attract homebuyers and can provide transitional housing and supportive communities for the most vulnerable among us. Savvy policymakers across the country are partnering with the design and modular construction communities to ensure that these additions to local neighborhoods are affordable, beautiful, and sustainable.

As in most of the US, affording a place to live in Salt Lake City is becoming increasingly difficult. Leading up to the Great Recession, home prices became over-inflated, contributing to the global financial crash. Immediately following, home prices fell due, in part, to widespread foreclosures leading to a surplus of homes—at the expense of thousands of displaced families.

Since then, home prices have risen to the point that they are way out of reach to most. A recent study in Utah found that the median-priced home was unaffordable to roughly 60 percent of households in 2019. By 2021, that number had fallen to less than 52 percent. This shift is was more pronounced among renters looking to buy.

Coupled with the housing crisis comes a rise in individuals and families experiencing homelessness. Housing costs were rising before 2020, and the COVD-19 pandemic made it worse. Breakdowns in the global supply chain caused prices of building materials to skyrocket. More people were working from home and remodeling. Many white collar employees chose to leave large, expensive cities for more affordable places like Salt Lake City.

Despite rent relief and eviction moratoria, an increasing number of individuals found themselves in financial uncertainty and unstable housing situations. Or out on the streets.

Rethinking policy and permitting

These complex crises caused policymakers across the country to rethink their approach to housing and the unhoused. In built-out cities, this includes ways to increase density. In Salt Lake City, as in other cities, one approach is to increase the stock of naturally occurring affordable housing. ADUs, while not a panacea, constitute one piece of a larger policy suite to increase the stock, diversity, and affordability of housing.

Small, standalone ADUs are commonly placed in neighborhoods zoned for single-family homes. To combat the housing crisis in California, five bills were signed into law in 2019 that eliminate restrictions on ADUs statewide and require faster permitting. Smoothing the regulatory path to ADUs helps keep housing more affordable by increasing supply.

While ADUs have been permitted in Salt Lake City, the administration examined the permitting and construction processes to see where they can be simplified or changed to increase accessibility. The longer-term goal is to create a library of pre-approved ADU plans, which could greatly speed up the permitting process.

The Plús Hús (at left) ADU by Minarc (Photo by Art Gray Photo) and the Lean-To ADU by Jennifer Bonner/MALL (at right) are preapproved by the City of Los Angeles Standard Plan Program.

ADU and Tiny Home Libraries

This idea of an ADU library is borrowed from a handful of other cities that have similar programs, including the Los Angeles ADU Standard Plan Program. In Los Angeles, there are 42 standard plans chosen for their sustainability, affordability, and architectural design. The initial plan review has taken place, so plans are approved and ready for site-specific reviews. The library cuts through much of the red tape and makes a potential ADU more affordable for the owner. Primarily, it streamlines the process. Salt Lake City is currently working through what a similar program would look like here.

The City of San Jose maintains a list of a dozen pre approved vendors and many designs. Nearby, the County of San Mateo helped establish a nonprofit to support homeowners adding affordable ADUs in the Bay Area. Across the Bay, the City of Fremont promotes just a few preapproved designs. Residents interested in constructing an ADU on their property can go to the website and pick a plan that fits their property. Then the homeowners contract directly with the designer. All preapproved plans still require additional site-specific plans, studies, and engineering, as applicable.

ADUs meet the needs of many for rental income or housing extended family; hence the term, “granny flats.” But they don’t work as well as transitional housing to help people off the streets. This is where tiny home cottage communities come in. Salt Lake City sees temperature extremes in both the summer and winter, and emergency shelters do not meet the needs of everyone. Even the increasingly popular conversion of existing motels into transitional housing continues to fall short.

But a standalone tiny home—a place of one’s own—can meet the needs of individuals experiencing homelessness, in different ways from multifamily housing. This is especially true when tiny homes are grouped in communities. Communities facilitate trauma-informed housing, which allows individuals to have their own place, without shared walls and hallways, which may be triggering to certain individuals. But these communities don’t currently exist in Salt Lake City.

Salt Lake City Design Competition

Enter the Empowered Living Design Competition. In 2021 Salt Lake City launched a design competition, seeking input from the design and architecture communities on ways to reimagine small-scale living in tiny homes and ADUs. Along with competition partners the Community Development Corporation of Utah (CDCU) and the American Institute of Architects Utah Chapter (AIA Utah), the city accepted submissions, and a panel of jurors reviewed and scored the designs based on five key criteria: Accessibility, Affordability, Durability, Livability, and Sustainability.

Entrants submitted either an ADU design (maximum 650 sqft) or a tiny home design (maximum 400 sqft), which could include a cluster of small cottages. Adaptability to various sites was key. And creative thinking about living space (both communal and individual) was viewed favorably.

The jurors were impressed with the creativity and innovation that designers brought. A common thread was modularity or pre-fabrication. Prefab saves both costs and waste in the construction process and can mean tighter construction in the controlled conditions of a factory. Modular construction is measurably more sustainable than conventional construction, considering impacts from material production and transport, off-site and on-site energy use, worker transport, and waste management. The Empowered Living entries highlighted barriers in current ADU policy and presented potential solutions, creating learning opportunities for the city.

The winners:

Grand Prize, ADU Category

Birch 1—Woofter Bolch Architecture

Runners-Up, ADU Category

Vested ADU—Process Studio PLLC

Guerilla Urbanism—Yixuan Lin

Grand Prize, Tiny Home Category

DAHLIN Concept—Dahlin Group

Runners-up, Tiny Home Category

Plug and Play—ajc architects

House with a Corner Eave—Cho & Urano

MOD HIVE Tiny Home Community

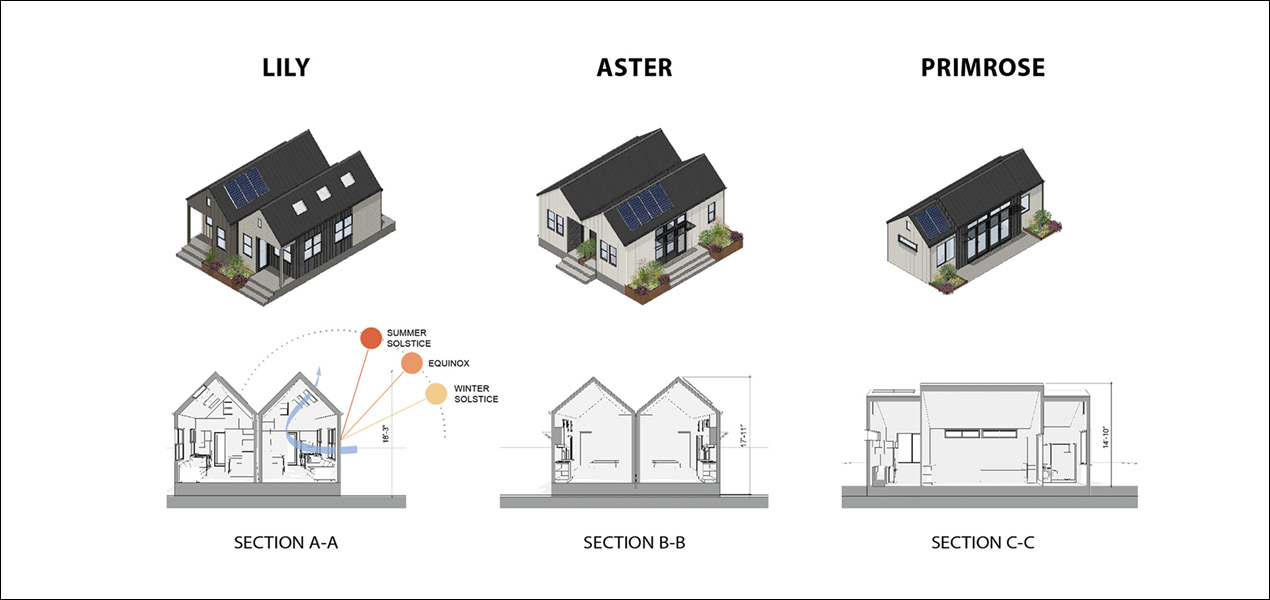

I’m highlighting the grand-prize–winning Tiny Home design for its cluster concept and extensive sustainability measures. The MOD HIVE community by DAHLIN Group is an all-electric, modular design intended to limit construction waste. Designed to a real, existing site that is typical of Salt Lake City, MOD HIVE lot configurations are flexible.

The site plan creates a tiny village with space for a community garden, outdoor gathering space, and barbecue/firepit. The sense of place encourages community. Trees provide shade in summer, while native, drought-tolerant plants are used in landscaping to minimize water use and create habitat for pollinators. Rain catchment is included in the design, creating small rain gardens and then a central rain garden; together they capture runoff.

The three tiny home designs respect the overall feel of Salt Lake City single-family detached homes and present a somewhat familiar aspect to the street. Steep roof pitches allow for vaulted ceilings that help make these tiny homes feel larger than their square footage. “A key objective for the MOD HIVE team was to create a highly flexible and cost-efficient prototype that is easily adaptable to a variety of sites and contexts, while never sacrificing a sense of community,” said DAHLIN Principal Brett Bailey.

Passive House Concepts

Passive design elements in the tiny homes include tightly sealed building envelopes; increased glazing to the south to admit the winter sun; reduced openings on west-facing sides; and double-pane, high-performance glazing to the west, north, and east. Sustainable forestry ensures that wood siding sequesters carbon on-site and enhances biophilia.

Operable skylights admit natural light and provide ventilation, while shading devices and programmable thermostats emphasize occupant comfort. Tile flooring acts as a heat sink, absorbing heat during the day and releasing it at night. Porches, porticos, and other shade structures block the summer sun.

The design takes advantage of solar panels on individual units and on the shared pavilions. LED lighting and high-efficiency electric appliances help achieve net-zero energy.

While this competition has ended and winners were announced, this is just the beginning. Salt Lake City intends to see some of these designs, as well as other designs, built into usable housing. (Check out all the winning designs.) As we move toward the goal of creating a more sustainable, more affordable, and more equitable housing system, we will continue to seek out innovative and creative solutions.

The author:

Blake Thomas is the Director of the Department of Community and Neighborhoods for Salt Lake City, where he oversees Building Services, Housing Stability, Planning, Real Estate Services, Transportation, and Youth & Family Services divisions.

Prior to working for the city, Thomas held various positions at the State of Utah and Salt Lake County, including county Economic Development Director and Executive Director of the Salt Lake County Redevelopment Agency. Thomas is a graduate of Utah State University, where he earned a bachelor’s in environmental studies and a master’s in Human Dimensions of Ecosystem Science and Management.