Unequal Scenes – Durban, South Africa photo by Johnny Miller licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

Nurturing trees and plantings in areas with the most need is critical to mitigating the worst effects of climate change

By Brian Libby

Whether in rural, suburban, or urban areas, or deep in the forest, trees remove carbon dioxide from the air, store carbon in the trees and soil, and release oxygen into the atmosphere. Most scientists agree that planet-wide reforestation is a potent weapon in reducing carbon in the atmosphere. But even in cities and suburban yards, well-placed trees can make your home and neighborhood more comfortable, healthier, and less-expensive to live in.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, the past 8 years were the warmest on record globally, driven by ever-rising greenhouse gas concentrations and accumulated heat. As trees grow, they sequester and store carbon in their accumulated tissue.

Carbon sequestration is the process where trees absorb CO2 during photosynthesis and store it in the form of woody biomass in the trunk, branches, leaves, and roots. Trees that grow quickly (such as saplings, pines, poplar, aspen, etc.) take up more carbon dioxide at a faster rate. Carbon storage keeps carbon out of the atmosphere. Hypothetically removing the water, about 50% of the mass of a tree is carbon. Trees can hold on to carbon for a long time and store carbon in surrounding soil. Wood in houses and furniture can store carbon for decades, as well. Wood will decompose eventually, releasing CO2 back into the atmosphere—very slowly.

In addition, trees and plants help cool the local environment, making homes and neighborhoods cooler in the face of rising temperatures.

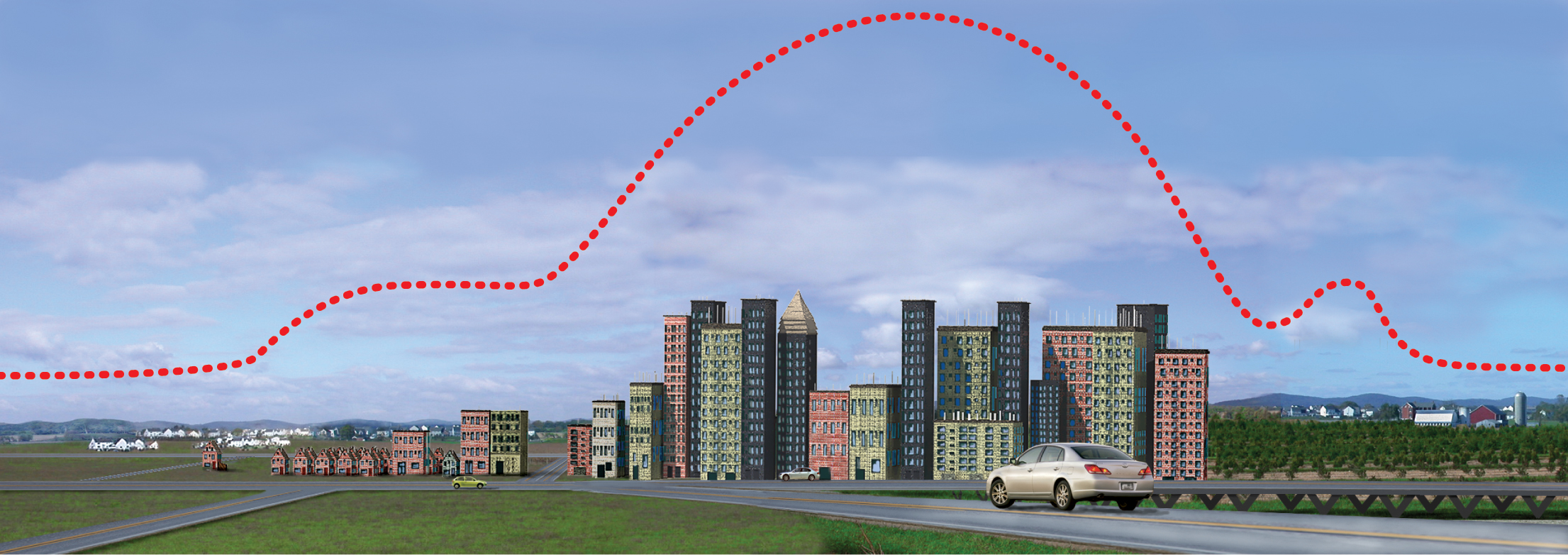

Surface temperatures in densely developed cities tend to be elevated in comparison to surrounding areas with more trees and green spaces. Image courtesy NASA.

Cooler Cities

Trees reduce the heat-island effect: the tendency of urban spaces to be warmer than surrounding rural areas, as the sun heats masses of concrete and glass. On the hottest summer days, shaded urban spaces can be as much as 20 to 45 ℉ cooler than unshaded areas. During sunnier seasons, a tree’s leaves and branches prevent about 70% to 90% of solar radiation from reaching the ground beneath them.

Trees also engage in evapotranspiration. Trees absorb groundwater, using water’s electrostatic force to bring nutrients up to the branches and leaves and then evaporating water off the leaves to create a pump, bringing up additional water and minerals. (Water also takes part in photosynthesis.) As sunlight strikes the leaves, water vapor is released into the atmosphere, cooling the tree and the surrounding air. A large oak tree can give off the equivalent of 40,000 gallons of water per year.

Trees save energy, aid the environment

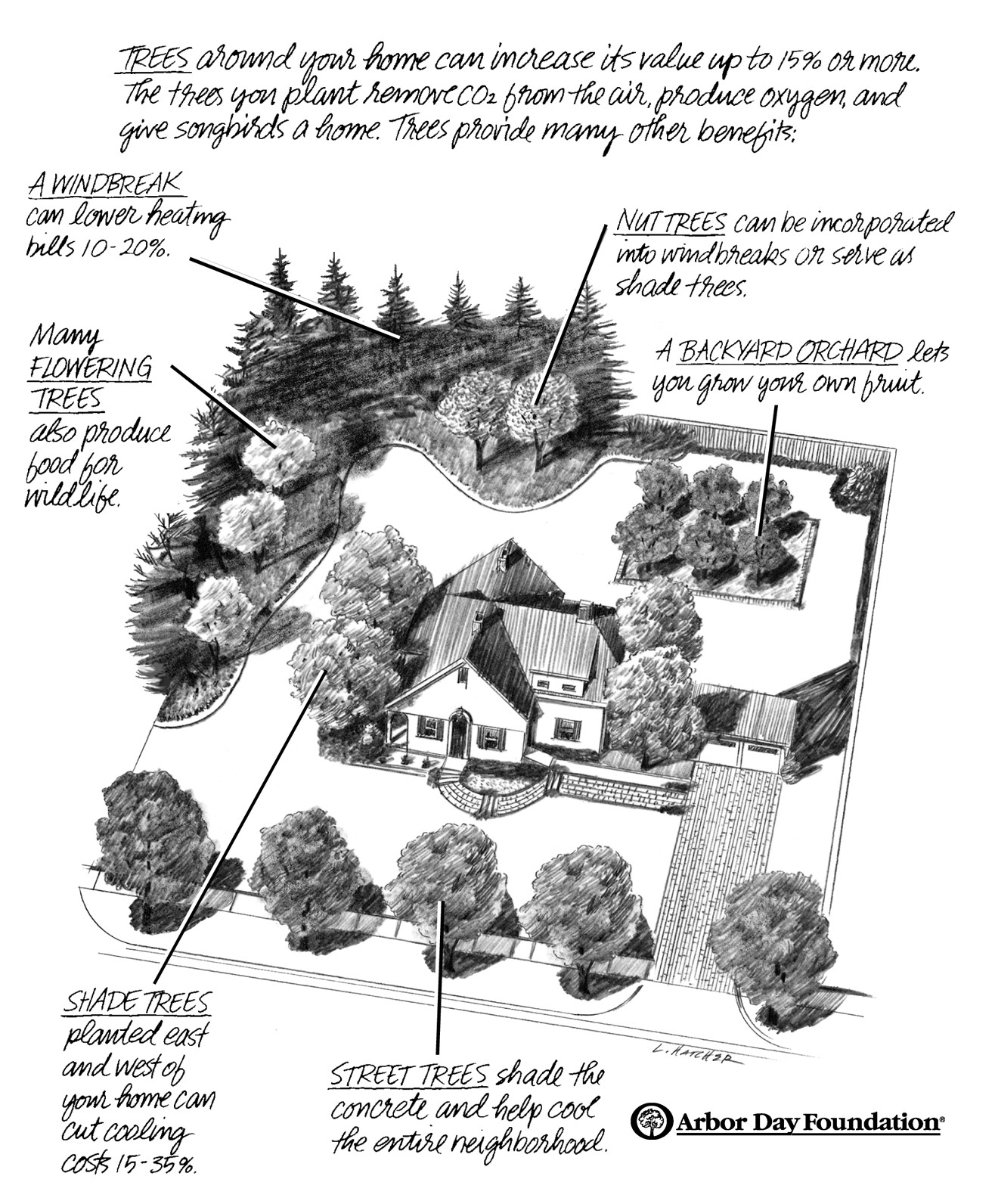

Trees reduce our energy bills mainly via shading and evapotranspiration. According to the US Department of Energy, trees placed to shade a house can reduce energy costs by 25 percent through a variety of mechanisms. In temperate climates, deciduous trees provide shade in the summer but let the sun’s warmth through in the winter. In other climates, different kinds of trees can shade year-round, provide windbreaks, shade south-facing windows, etc.

“That’s why we use the term ‘energy-saving trees,’ ” said Pete Smith, who oversees urban forestry for the nonprofit Arbor Day Foundation. Plantings reduce air-conditioning loads, lessening that source of heat gain in densely populated neighborhoods and reducing dependence on local, polluting gas-fired peaker plants. “Sacramento found they could avoid having to build a new power plant simply through the act of planting about 1,000 trees,” Smith added. In addition, trees improve local air quality by absorbing urban air pollutants, like ozone and sulfur dioxide, and capturing particulate matter that can harm respiratory health.

Planting trees and other ground-level native plants also helps encourage biodiversity. A 2019 Cornell University study found that since 1970, North America has lost approximately 2.9 billion birds. When one species loses habitat, many other species will also decline. In addition to birds, insect populations are also vastly down, affecting a range of species.

Native trees are vital to attracting wildlife because they have developed interdependence over thousands of years. And compared to grass lawns and imported trees, native plants are likely more suited to local rainfall patterns. Native plants also reduce the need for pesticides and herbicides, which can decimate insect and animal populations.

Where to Plant

For deciduous species, planting a tree on the west side of your house is typically the most effective for summertime cooling, specifically if the canopy shades windows and portions of the roof. Another effective spot is to the south, but there is a tradeoff. In cold and temperate climates it’s best to allow wintertime sunlight to reach those south-facing windows and reduce the need for mechanical heating. In communities, shading parking lots and public sidewalks, as well as schools and commercial storefronts, have also been found to reduce overall neighborhood temperatures.

Trees are not the only tool in the toolbox. Just as a forest is an ecosystem of trees and ground vegetation, a combination of other plants can help increase a tree’s climate-control effectiveness. In restricted settings where tree-planting is not possible, vines may grow on a façade to reduce heat gain, or shrubs and bushes can effectively block solar radiation from windows. Consider shading air-conditioning equipment, to maximize efficient operation, while ensuring proper airflow around the unit.

At the perimeters of residential properties, particularly sidewalks and streets, trees and their canopies often compete with utility poles and lines. The Arbor Day Foundation recommends planting small trees (25 feet tall or less, at maturity) at least 8 to 10 feet from a wall, or 6 to 8 feet from the corner of your home. Medium-sized trees (up to 40 feet at maturity) should be placed at least 15 feet from walls and at least 12 feet from the corner. Large trees should go at least 20 feet from a wall and 15 feet from the corner.

Social Justice and Urban Forestry

In recent years, urban forestry has changed its focus and approach. Studies show that the most advantageously large and mature tree canopies tend to exist in higher-income neighborhoods, while lower-income neighborhoods and communities of color often see the lowest percentages of urban tree cover.

“We have spent the last couple of decades in urban forestry taking a top-down approach that was mostly about data,” said the Arbor Day Foundation’s Smith. “It’s given us better tools to inventory the trees that we manage, better satellite data to look at cities from above and give accurate canopy-cover assessments. But the engagement piece with communities has been missing. It’s only really been in the last 5 to 10 years where environmental justice in particular has taken a front seat.”

To successfully grow cities’ tree canopies, Smith says, trees must be not just planted but cared for, by both professionals and local volunteers working collaboratively. “It won’t be because the city came and hired a contractor to plant new trees. I think the engagement piece, while it is some of the hardest work to do, is probably the most critical if we’re going to ever achieve these longer term benefits.”

As we quantify the impacts on low-income neighborhoods and public health, we may be entering an urban-forestry renaissance. Earlier this year, Congress passed and President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, which includes a historic re-investment in urban forestry programs across the nation.” We have disinvested in tree programs for so long,” Smith said. “This is a turnaround.”

The author:

Brian Libby is a Portland, Oregon-based design and arts journalist. He has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Architectural Digest, Dwell, and Metropolis, among many others. You can find him at brianlibby.com.

Our team researches products, companies, studies, and techniques to bring the best of green building to you. Elemental Green does not independently verify the accuracy of all claims regarding featured products, manufacturers, or linked articles. Additionally, product and brand mentions on Elemental Green do not imply endorsement or sponsorship unless specified otherwise.

![10 Steps Toward a Zero Energy Home [Infographic]](https://elemental.green/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/cbfb-440x264.jpg)