Desert Rain images by Chandler Photography

Some of the links below are affiliate links, meaning at no additional cost to you, we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Thank you for helping us continue to bring you great content.

By Brian Libby

THE WATER SHORTAGE PROBLEM

Freshwater is becoming scarce. The United Nations projects by 2025 about 1.8 billion people in over 50 countries (including much of the southern and southwestern United States) will be affected. That’s why homeowners are increasingly looking to use water efficiently, and why today the term “net zero” isn’t just for electricity. Enter net zero water.

In 2020 alone, Americans spent just over $247 million on residential rainwater harvesting systems, a concept that’s been around since ancient times but gained traction in recent decades in commercial and institutional buildings to save water costs. But rainwater harvesting is just the first step. The next is reusing greywater from laundry, dishwashers, showers and tubs for irrigation or even to flush toilets. In many cases, that one-two punch can be enough to reach net zero water: the point at which you’re producing as much as you consume (or more).

LIVING BUILDING CHALLENGE AS THE ULTIMATE GOAL

While the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) green-building rating system has been around for over two decades, it has more recently added alternative water management systems as an integral part of the standard. Still, the ultimate sustainable seal of approval is arguably the Living Building Challenge, an international certification program created in 2006 by the non-profit International Living Future Institute to promote regenerative design.

LBC certification is broken down into seven performance areas, known as Petals: Place (or site), Water, Energy, Health and Happiness, Materials, Equity and Beauty. Full certification must address all seven petals, but projects can also receive what’s known as Petal certification for meeting three.

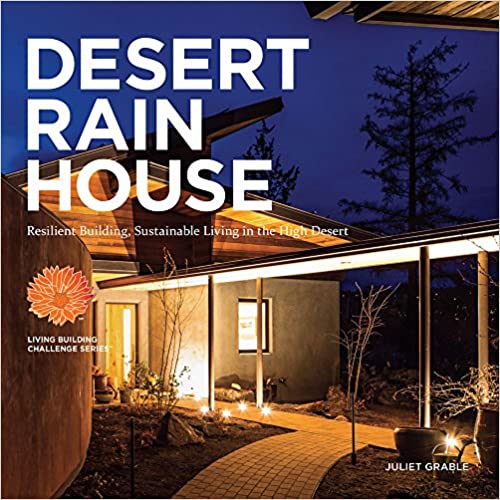

WATER WORKS: DESERT RAIN HOUSE

Bend, Oregon’s Desert Rain house became the first residence in America to earn full LBC certification in 2013. Today, it remains one of only three. (Though, it also happens to be LEED Platinum certified as well as Earth Advantage Platinum certified.) Its architecture and interiors were designed by local firm Tozer Design, with water systems by Seattle-based Whole Water Systems, and not a single drop of water, including wastewater and snow melt, ever leaves the site thanks to its combination of rainwater harvesting system, constructed wetland for blackwater, its greywater treatment system for re-use, and underground storage tanks.

Building in a dry, high-desert climate, lower-than-average rainfall made the task even more difficult, and all the more impressive. (Of note, Tozer Design practices a wholly sustainable approach to architecture and design, and founder Al Tozer has since served a stint as ILFI’s Education + Living Building Challenge director.) Even today, Desert Rain’s design offers lessons. Below, we talked with Morgan Brown, president of Whole Water Systems, to learn more about them.

Q: Bend averages 11 inches of rainfall a year, compared to 30 inches nationally. Were you confident you’d get enough water for Desert Rain?

A: We went back and got data on the last 20 years of rainfall in Bend. Our engineer took the worst of those 20 years, which was seven inches of rain. We knew rainwater harvesting was probably going to be our toughest challenge. We knew we needed to get as much roof area as possible, and it helped that this was a large multi-building compound. They committed to 40 gallons a day, which I’m happy to say they were able to beat fairly handily. They wound up building a large cistern into the foundation of the garage to draw from: 35,000 gallons.

Q: How does the constructed wetland work?

A: We’re really just doing what nature is doing: taking organic material out of the water with bacteria. Almost any wastewater system on the planet, whether it’s a giant sewer plant or our constructed wetlands, is really farming bacteria to eat that organic matter.

Q: We traditionally haven’t had wetlands or other water-treatment technology used in residential settings like this before. Is this the future?

A: Oh, absolutely. I’ll go so far as to say centralized water treatment and disposal: bad. Decentralized treatment and reuse: good. Anybody working in sustainability and resilience has known these mantras for decades. It’s really been in the last 10 years that the idea has gone more mainstream.

Q: What does net zero water mean to you?

A: At minimum, you’re talking about two things: drinking water and wastewater. Net zero means you produce one hundred five percent of what you use.

Q: Would you recommend pursuing Living Building Challenge certification, particularly the water Petal?

A: I think it’s a great thing to do. I have personally built houses for myself doing those things. It’d be cheaper than when Desert Rain was built, and certain things with code ought to be way easier. But you’ve got to check your values and your pocketbook. If somebody goes into it assuming they’ll be able to do it for the same cost as not doing it, we’re probably not there yet.

Q: Could you walk us through Desert Rain’s water systems?

A: There’s a rainwater catchment for drinking water, the blackwater system for treating the human effluent, and a greywater treatment for everything except the dishwasher and the toilet. And really the three systems don’t really touch. Mostly one flows into the other in some cases.

It’s essentially just catching water off the roofs, channeling it with some filtration into a large cistern and then keeping that fresh and filtered and bringing it back in the house for drinking. In the recirculation, there is micro filtration between two chambers within the tank, and UV filtration before it comes in to be consumed.

In terms of treatment, this constructed wetland is kind of like a greywater system on steroids. We have a septic tank at the end of the constructed wetlands that’s a little bigger than what you would have for normal wastewater: 1,500 gallons. But it was important, because if we’d put one drop of water back in that sewer system, the Living Building Challenge certification would have been off.

Q: Which of these systems can you see being the most applicable to the average homeowner?

A: Treating your own wastewater is not going to be an option for most people in an urban environment. If you’re really talking about something where you want to meet a bunch of your needs, get into anything like a net zero, you’re going to be doing a pretty sophisticated rainwater harvesting system. And the good news is that that’s allowed in a lot more places, as is greywater filtering. The good news is there are a lot more contractors who are doing that.

“If we’d put one drop of water back in that sewer system, the Living Building Challenge certification would have been off.” —Morgan Brown, President, Whole Water Systems

Desert Rain Design Team:

- Builder: Timberline Construction

- Architecture + Interiors: Tozer Design

- Water System Design: Whole Water Systems

- Landscape Design: Heart Springs Landscape + Wintercreek Restoration

- Sustainability Consultant: Vidas Architecture