Now Updated for 2024!

By Nathalie Gee

Every chemical substance has a defined composition and characteristic properties. Some occur naturally, while others are manufactured. The word chemical carries a negative connotation, but hey, water and table salt count as chemicals. That said, we inhale, ingest, and come in contact with many toxic chemicals in our daily lives, even inside the refuge of our homes. But by making informed decisions about home building materials and operations, we can reduce our exposure to toxic chemicals and avoid the negative impacts.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has created a list of chemicals that are Persistent, Bioaccumulative, and Toxic, which are proven harmful to people and the environment. The EPA currently tracks and regulates more than 700 individual chemicals and 33 categories of chemicals in its Toxic Release Inventory (TRI); however, this list does not include all known toxic chemicals.

What’s bioaccumulation?

Some chemicals pose acute risks, while others can impact organisms over time. Look for news of emerging chemicals, such as “forever chemicals” like per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), that have not been fully studied or regulated. Forever chemicals are those that do not break down in an organism or the environment.

Bioaccumulation occurs when an organism absorbs more of a chemical than it can break down or excrete. Toxins that bioaccumulate, over long or short periods of time, increase our risk of harmful health impacts, even if the levels of that toxin in our environment are not high. Biopersistence, a related phenomenon, most often refers to the ability of a microfiber or particle to lodge in the lung or throat, such as in the context of fiberglass and asbestos.

Dust!

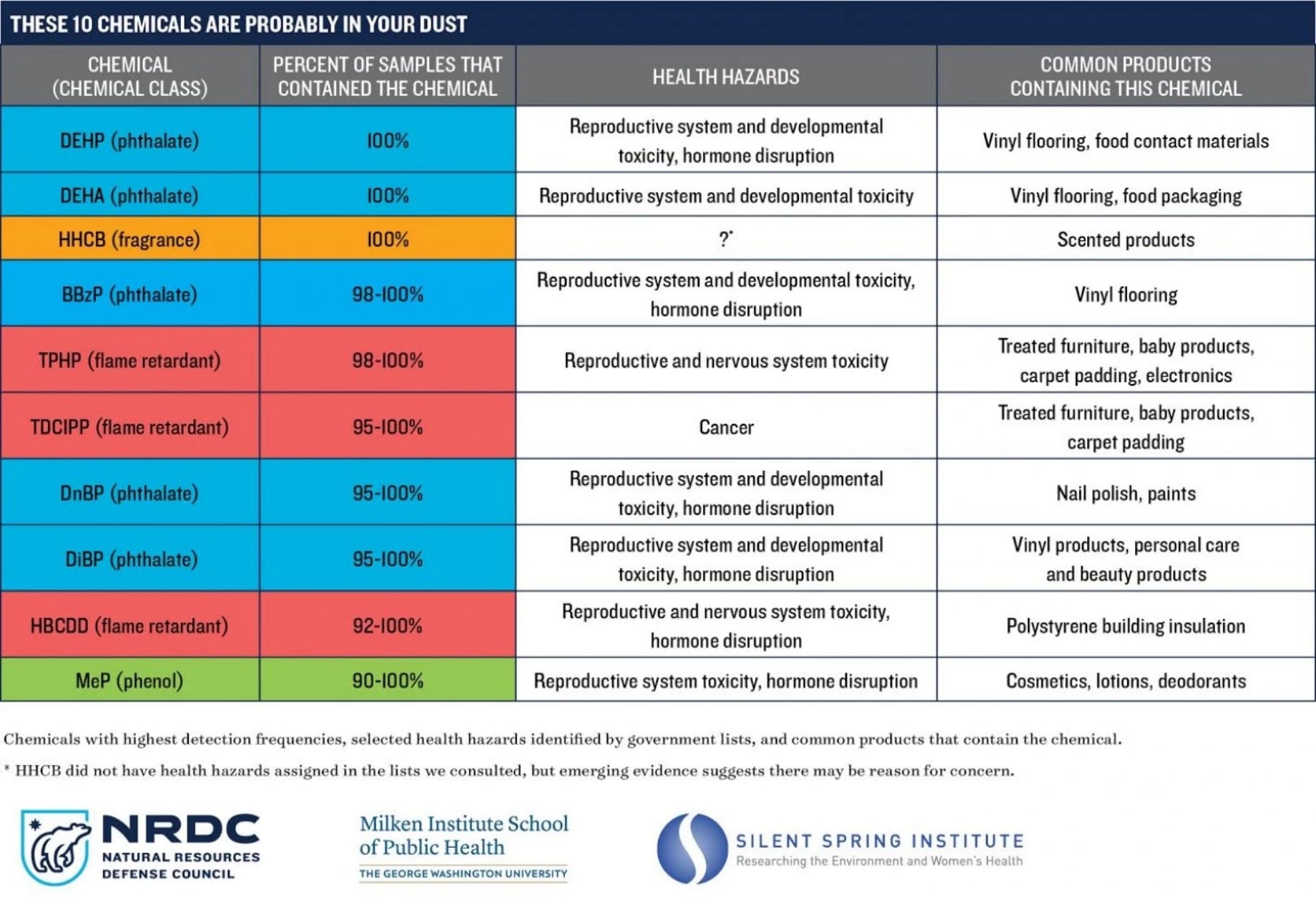

Regular dusting and vacuuming can help reduce exposure to dozens of toxic chemicals found in dust. We generally spend over 90% of our time indoors exposed to materials from building materials and consumer products. Furniture, electronics, personal care and cleaning products, and floor and wall coverings contain chemicals that can leach, migrate, abrade, or off-gas from these products and materials. Consequently, chemicals such as phthalates, phenols, flame retardants, and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFASs) are widely detected in the US general population, including vulnerable populations such as pregnant women and children. Exposure to one or more of these chemical classes has been associated with harmful health effects, including reproductive toxicity, endocrine disruption, cognitive and behavioral impairment in children, cancer, asthma, immune dysfunction, and chronic disease.

Studies have shown that indoor dust can contain these hazards in startling concentrations. To limit harmful dust exposure, use a vacuum with a HEPA filter and change it frequently. Use a wet mop to clean uncarpeted floors and wipe surfaces using a cloth. Remember to wash hands often when you’re at home, especially before eating.

Let’s break down the most common toxic chemicals you do not want in your home: health impacts and how to mitigate risks

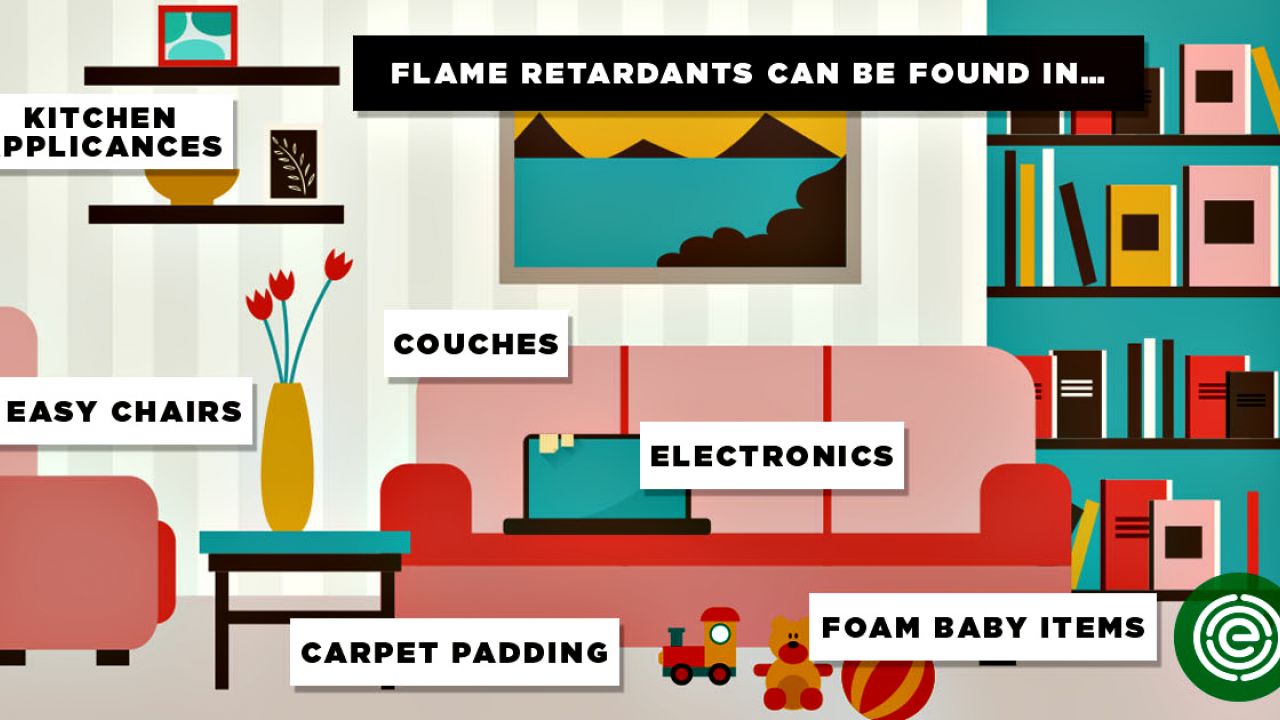

Flame retardants can be found in old and new products. © Environmental Working Group

Flame retardants

There are many types of flame-retardant chemicals, but the most common include polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and halogenated flame retardants (HFRs). Flame retardants are especially common in furniture, cushions, mattresses, and carpets. They’re also found in plastics and other textiles.

Studies have linked flame retardant chemicals to cancers, thyroid disease, and decreased fertility. People are most often exposed to flame retardants as they migrate out of foam furnishings and settle into dust, which is then ingested.

One way to mitigate risks from flame retardants is to replace old foam products and furniture, especially furniture that predates 2005. Today, many flame-retardant options do not use toxic chemicals. Do not reupholster old furniture or replace carpeting yourself.

Forever chemicals

Polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), are found in many consumer goods to make them water-, stain-, and grease-resistant. We are exposed to PFAS most frequently by ingesting contaminated food or drinking water, or via PFAS in dust and consumer products.

These are bio-persistent, bioaccumulative chemicals that are still being studied with regard to their harmfulness to humans, though they are likely a human carcinogen. They are shockingly prevalent in many consumer goods. A growing body of evidence has linked PFAS to increased risks of cancer, thyroid issues, asthma, allergies, liver damage, and decreased fertility.

The best way to avoid PFAS in home building materials is to avoid stain- and water-resistant carpeting and flooring. Consider non-toxic and naturally stain resistant rugs and lead-free tile as flooring alternatives. You can also reduce PFAS exposure in your home by tossing our old Teflon and non-stick pans, dusting frequently, and filtering drinking water.

Graphic courtesy of the City of Riverside

PVC

Chlorinated polymers constitute another class of chemicals to avoid diligently. Polyvinyl chloride (PVC, also referred to as vinyl) is one of the most prevalent types of synthetic polymers, and hides all over the home: in flooring, pipes, wallpapers, roofing, upholstery, and waterproofing membranes. Phthalates (often called plasticizers) are a group of chemicals commonly added to plastics like vinyl to make them less rigid and increase longevity. You’ll also find them in many consumer goods like shampoos, cosmetics, and toys.

Studies have shown that phthalates can be endocrine disruptors, and vinyl chloride, a key ingredient in PVC, has also been linked to cancer. Other materials added to PVC include lead and cadmium: heavy metals that can be toxic in elevated concentrations, especially to children.

One way to reduce exposure to phthalates and chlorinated plastics is to look for biobased plastics or naturally-derived products. Additionally, clay, glass, ceramics, wood not treated with PVC or finishing materials, and linoleum all form non-toxic building alternatives.

Formaldehyde

Formaldehyde can be found in pressed wood products such as particleboard, fiberboard, OSB, and plywood paneling: these are built into furniture, subflooring, cabinets, and more. Urea formaldehyde foam insulation was commonly installed in the 1970s and 1980s and is now banned. Formaldehyde belongs to the family of indoor VOCs (volatile organic compounds) that may pose a hazard when inhaled. Some manufacturers treat home textiles with formaldehyde, such as permanent press draperies. Check for formaldehyde in adhesives and glues, and in the preservatives in painting and coating products.

Formaldehyde is a known human carcinogen and respiratory irritant. Immediate impacts of inhaled formaldehyde can include watery eyes, irritation to the nose and throat, and nausea.

VOCs

VOCs are found in many products in the home, including in paints, varnishes, caulks, flooring, upholstery, adhesives, and foams. Additionally, air fresheners and cleaning products may degrade indoor air quality. VOCs (volatile organic compounds) most often have a strong odor, because they turn from a solid to a gas at room temperature, a process known as off-gassing. Breathing in large amounts of VOCs can cause eye, nose, and throat irritation, while high levels of VOCs can cause kidney, liver, and central nervous system damage. EPA only regulates outdoor-air VOCs and does not have the authority to regulate VOCs that present indoor-air risks, even though VOC concentrations indoors can be up to 10 times higher than outdoors.

To reduce your exposure to VOCs, consider non-toxic paints and varnishes. Look for home furnishings that are solid wood with low-emission varnishes, or that have off-gassed in the store already. UL’s GREENGUARD Gold Certification tests for potential airborne contaminants and requires low total VOC emissions. Try increasing the amount of fresh air in your home via ventilation and climate control to help reduce indoor VOC concentrations. Open windows or doors when outdoor air quality is good, and use fans to circulate air from outside.

Formaldehyde can be found in furniture, subflooring, cabinets, and more. “Particleboard” image by Rotor DB is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED.

Heavy Metals

Inside your home, lead typically presents as dust from flaking or chipping lead paint. Lead can also be found in old pipes and it can leach into drinking water. In 1986, Congress banned the use of lead in pipes, however older construction homes may have lead in their plumbing.

Manufacturers use arsenic, specifically chromated copper arsenate (CCA), in many pressure-treated wood products as a preservative. Note that CCA-treated wood often has a greenish hue. In 2003, the US EPA and the lumber industry agreed to stop using CCA-treated wood in residential construction. However, homes built before 2003 may contain CCA-treated wood, as well as outdoor structures like decks and playgrounds. Alternatives to CCA-treated wood include heat- or pressure-treated lumber, wood alternatives, and composite materials such as steel, fiberglass-reinforced concrete, or pest-repellent wood species.

PVC sometimes contains heavy metal cadmium, and it can be found in some metal coatings, batteries, and pigments. There are numerous potential sources of household mercury, specifically home furnishings such as antiques like vases and mirrors, as well as old models of electrical appliances like furnaces, water heaters, and ovens.

The term heavy metal refers to any metal that has a high density and is toxic or poisonous at low concentrations. Arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, and mercury are among the most common heavy metals found in domestic applications, and are known to induce multiple organ damage, even at lower levels of exposure. Handing heavy metals may cause skin irritation and respiratory issues. They’re also considered known or probable human carcinogens. Many heavy metals may bioaccumulate in people and pets, reaching toxic concentration more intense than ambient environmental levels. To mitigate exposure risks, consider updating old appliances.

Asbestos

Asbestos lurks in many parts of the home, including in attic and wall insulation, roofing, vinyl floor tiles, some textured paints, heat-resistant fabrics, fire-proofing materials, and coated pipes. People usually get exposed to asbestos through inhalation of degraded asbestos-containing materials, so asbestos that is undisturbed is not a health hazard.

A mineral fiber that is resistant to both heat and corrosion, asbestos particles that lodge in the lungs are a known human carcinogen, increasing the risk of lung disease, lung cancer, mesothelioma, and asbestosis. Many countries have banned the use of asbestos, however asbestos remains legal in the US. Consider using natural, non-toxic insulation like formaldehyde-free mineral wool.

Antimicrobials

Antimicrobials marketed with a healthy-for-your-home claim are highly prevalent today, especially because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We find antimicrobials in domestic applications ranging from soaps to building materials, countertops, and paints. Antimicrobials are often used as a preservative in building materials.

Overuse or misuse of antimicrobials can lead to antimicrobial resistance, rendering some drugs and treatments no longer effective. Science has not yet substantiated many of the health claims about efficacy. You’re wise to use antimicrobial products prudently, as their primary use case is for vulnerable individuals and those with weakened immune systems.

Not all chemicals are bad

Researching the chemicals you bring into your home and making informed choices about materials for construction and renovations are important steps toward mitigating potential harmful effects from poor indoor air quality and dust. The International Living Future Institute’s Living Building Challenge Red List is a great resource: it calls out chemicals, materials, and elements known to cause adverse effects on human health and the environment.

The author:

Nathalie Gee is an environmental consultant based in New York City. She is a graduate of Barnard College of Columbia University, where she majored in environmental science. She is a frequent contributor to Elemental Green and Zero Energy Project and focuses on sustainability and climate topics.

Our team researches products, companies, studies, and techniques to bring the best of green building to you. Elemental Green does not independently verify the accuracy of all claims regarding featured products, manufacturers, or linked articles. Additionally, product and brand mentions on Elemental Green do not imply endorsement or sponsorship unless specified otherwise.